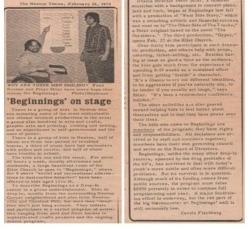

I somehow learned that the owner, whose name I don't recall, was looking for shows to produce that would help establish his new venue as a legitimate theater. I approached him and asked if we might give one performance of my showcase, consisting entirely of my own songs, on his stage. The idea was that if he liked what he saw, he'd mount the showcase as a full-fledged Off Broadway musical at the theater.

He agreed, and the kids and I performed our musical numbers, and some brief bits of connecting dialogue I had hastily written, to an audience of mostly parents and industry people. I recall that the audience seemed to genuinely like my songs. The overwhelming feedback, however, was that without a major adult story line, the songs alone would never generate an audience.

I went home unsettled, but with a gut feeling that I could do this. Over the next few months, I continued my showcases, discussion groups, and piano playing, but found myself increasingly distracted and frustrated as to how to go about writing a "major adult story line".

Then, one morning I woke up with an idea that literally made me laugh out loud. To this day, I marvel at how it eluded me for so long, especially since I had inadvertently stumbled on the well-known creative axiom: "You write what you know".

That morning, Benny Rosen, Junior was born. An aging former Vaudevillian and children's coach, Benny lived and worked in a small, museum-like studio in New York's Times Square neighborhood. The idea of writing a story about this old man and his young students was tantalizing. It seemed like the perfect idea- something I felt I related to, could easily write, and would personally like to see on a stage.

After playing with some dialogue, however, I came to what should have been an obvious conclusion: I had a good main character, a good situation, and some good songs, but no story line whatsoever, and no clue how to write one.

Over the next couple of years, I hired and fired a series of writers. I was hoping desperately that one of them would basically write the show for me. Unfortunately, none of them created anything I wanted to use. It soon became terrifyingly clear that if I wanted to tell Benny's story, or mine, as it were, I would have to write it myself.

Our audiences had slowly dwindled at the Comic Strip, and my Professional Children's Revue had come to an end. Still, I kept my Broadway hopes alive by holding on to a small group of talented students who were willing to continue rehearsing my songs, along with experimenting with dialogue and scenes.

The title had become The Kid Who Played the Palace, and my ambitions had evolved beyond Off Broadway.

Despite having no story, nobody to write one, and no money to speak of, I had succumbed to an inner whirlwind of fantasy and wishful thinking.

I began announcing to anyone who would listen that I was producing The Kid Who Played the Palace for Broadway.

To this day, I believe I just might have done it, and well within that average eight-year window, if it hadn't been for a phone call in April, 1984, from none other than Ray Diamond of Camp Lokanda.

Ray knew I was coaching kids in New York and, by then, Westchester County, and he presented an idea. He suggested I organize a resident musical theater clinic that would take place at his camp, immediately following his regular season.

At first, I turned him down, viewing this as a distraction from my work on my show. I had no idea how accurate that was. That "distraction" would last more than thirty-five years and counting.

My father had directed camps throughout my childhood, and I had grown up spending most of my summers in cabins surrounded by woods. The idea of being in charge of my own musical theater program in a camp environment proved irresistible. I called Ray and we began planning what was to eventually evolve far beyond the scope of a camp.

That phone call was the founding moment of both the Beginnings Workshop and my lecture career.

I remember my first lecture. The parents of one of our students informed me she owned a theater group somewhere in Tennessee, and offered to pay my expenses as well as a small fee if I would visit and speak to her students about the realities of a career in the industry. I had no experience with kids from the south, and all sorts of stereotypical images leapt to mind.

I eagerly accepted her offer. In the talk, I described the industry to the best of my ability, focusing mostly on my opinions and views as to which sorts of kids tended to reach success, and which didn't, and why.

Harvard met Broadway as I found myself weaving together such unlikely topic-mates as self-worth and the needs of New York agents and casting directors. In short, I asserted that the sort of kids that were most desirable in the industry were those who exhibited the confidence and openness that only a truly happy, self-accepting kid would have.

It was the first time I had ever said that, and the first time I had ever lectured about, well, anything.

It was also the last time I ever accepted payment for giving a lecture. I found I didn't need to. Several of those children, like thousands who would follow, ended up attending my workshops, which barely surpassed the cost of my trips, my rent, my workshops, and on a good week, maybe some Cuban cigars. I considered this more than adequate compensation, and still do.

The most interesting part of my visit to Tennessee was interviewing the kids, which immediately followed the lecture. Once again, I observed a few fascinating but superficial differences between kids from different backgrounds, such as their accents, which I found adorable, and yet far deeper similarities. It occurred to me even back then that the points I was making had importance that transcended show business.

A decade or so later, my workshops and lectures had evolved well beyond Ray Diamond's initial distraction. They had literally become my proverbial “day job”; I was lecturing to thousands of students each year from all parts of the United States, and eventually Canada, and directing workshops that would soon spread from New York to Hollywood and eventually London, England.

Although The Kid Who Played the Palace had been forced into the background, rarely a day went by that I didn't spend at least a few minutes working on a lyric, melody, or piece of dialogue. I had enlisted a brilliant and prominent Broadway expert and director named Bill Martin, (who sadly deceased in 2018) to dramaturge, and in 2004, we conducted informal stage readings of what was then a primitive script and score at the Emelin Theater in Mamaroneck, NY.

This was immediately followed by a semi-orchestrated demonstration recording of the songs.

Echoing my experience from twenty years earlier, the music was again well-received, but the general consensus was that the story line was weak.

After many more years of intermittent work, with continued input from Bill, I enlisted a friend and professional writer, Lee Stringer, to assist with story ideas and dialogue. Lee's input proved invaluable, and largely as a result, I decided it was at long last time to proceed with the show in earnest.

Which brings us to here and now.

This fall, winter, and spring, (2019-2020) I will be mounting pre-Broadway staged readings and backer auditions of the script and score of The Kid Who Played the Palace.

Fund-raising will begin in earnest, and I expect that my initial time estimate of “2-3 years tops” may not be that naive after all…that is, if we start the clock now.

To steal a phrase from Kander and Ebb: maybe this time.

Thank you for listening.

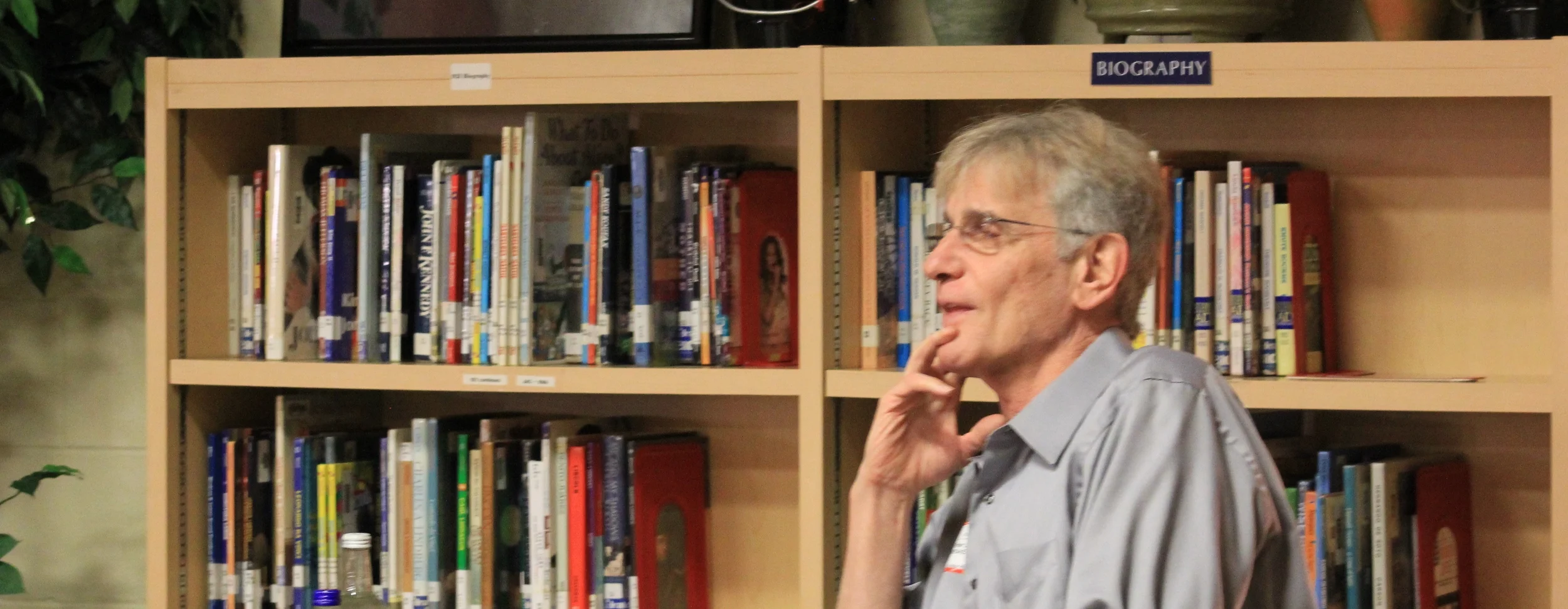

Peter Seidman