PART II: WHY I'M (Still) NOT A BROADWAY PRODUCER...

/Marilyn and I set up house together in my home town of New Rochelle, New York, and were eventually married.

The relationship lasted just over two years, before my own preoccupation with building a career, coupled with my own immaturity and preoccupation with, well, me, resulted in a separation and ultimate divorce.

This was a dynamic I would see repeated hundreds of times, without exception, with young people throughout my career. It's complete predictability led to one of my firm dictums to aspiring actors: arts careers and serious romantic relationships do not work with young people.

Marilyn had moved to Massachusetts, and about a year after the divorce, perhaps subconsciously following her, I moved there as well. I settled in the Boston suburb of Newton Corner, where I discovered a teen youth center called Beginnings, held in the basement of the Elliot Church of Newton. It was directed by a deeply caring individual named Fred Rosene.

Fred eventually wrote a book about that place entitled Making a Difference, which I was pleased to learn includes a great deal about my own work there.

Most of the kids at Beginnings had problems with school, home, and the courts, and were not welcome at many places about town. This made the center a social oasis for them. More than thirty years later, I can still hear the pounding of their fists on the large wooden outside door every day just before four o'clock pm, which is when the center opened.

There was absolutely nothing in my own background that suggested any sort of affinity with these kids. They were tough, physical, street-wise, and had as much use for theater as I have for a pair of nunchucks. But the place had a stage, and believing I had little else to offer, I was stubbornly determined to get those kids into some sort of musical production.

West Side Story seemed a perfect choice.

Volunteering my time, I started by persuading the most influential kids to join, and soon had a full cast of Jets and Sharks, along with Tony, Maria, and the others. The production opened to a clearly impressed audience of parents, community members, and church people. To this day, I am convinced we had the most realistic gang fights ever staged in the history of theater.

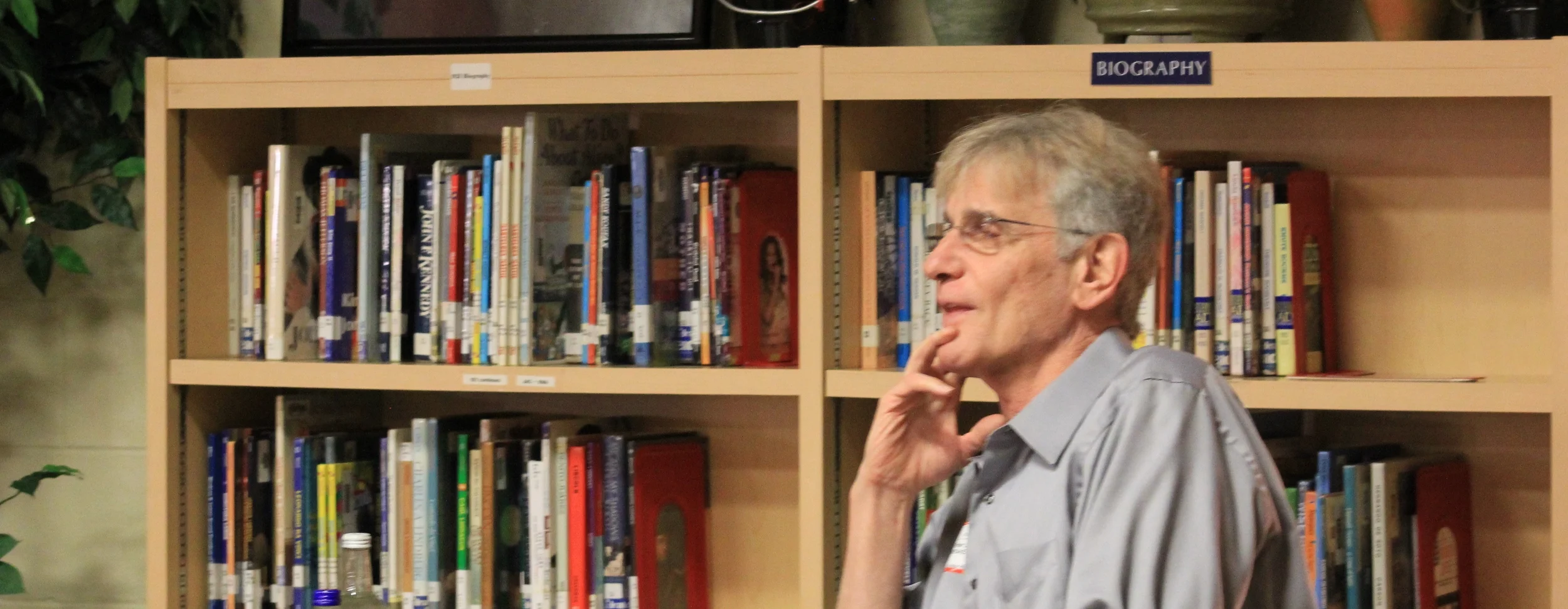

Fred Rosene and Peter Sklar, Beginnings Youth Center, 1975

West Side Story was followed by a series of other productions, including an original, albeit primitive musical of my own which I adapted from S.E. Hinton’s famous novel, The Outsiders. Given the kids I was working with, its gang clashes made it a logical choice.

Our success enabled the center to attract funding for my fledgling theater program, and I recall eventually being handed a check for $97 weekly for working more than 80 hours. It was the first money I ever received for working with kids. As much as I appreciated and needed it, however, I would have continued working with these kids for free.

It was enough for my ego back then to believe I was one of the few adults in their lives who could command their respect without representing any sort of physical challenge to them. I was even more proud of the fact that I was probably one of the few adults on the planet who, without offering them money or fame, could persuade them to sing, dance, and act in front of an audience.

I supplemented my meager Beginnings income by playing piano in a number of Boston restaurants, but realized I was becoming less and less interested in a career as a musician. I was instead increasingly fascinated by the prospect of using the arts as a vehicle to reach, well, unreachable kids. I was soon directing similar programs, with similar kids, in the Boston working-class suburbs of Cambridge and Dorchester.

Around this time, I was introduced to a summer camp director named Ray Diamond who invited me to be the Theater and Music Counselor at his private camp in the Catskills region of New York State, Camp Lokanda. The job paid well, and it was fun. I spent five summers there, 1973 – 1978, taking a seasonal break each year from my work with Massachusetts kids, somehow managing to stage and musically direct a different full- length musical production every week.

The grueling schedule notwithstanding, it was an invaluable experience in two respects:

1. I learned more about the structure of the libretto, script, and musical score of Broadway musicals those summers than at any time before or since.

2. Although the kids at the camp were from ostensibly stable, well-to-do families, I began to sense that many of them had emotional issues that ran deeper, and were more serious, than those of my Massachusetts “problem” kids.

Recently, I was saddened to learn of Ray’s passing. What I remember most from the theatrical crash course he provided, was the budding realization that I wanted to write and produce a musical of my own- one that would make a meaningful statement about kids.

My increased interest in theater, along with pressure from my parents to continue college, led me to enroll at the University of Massachusetts’ Dorchester campus, with a double major in theater and psychology. This, too, lasted only two years which I attribute partially to the fact that, probably based more on arrogance than truth, I felt I wasn’t learning much more than I had already taught myself directing community and camp theater.

Again, I dropped out of college, but not before managing to direct and mount a full-scale, totally illegal school production of Grease, which was playing on Broadway at the time. The show ran two nights. We had full houses and made about $2,000 at the box office, which I was told was unprecedented. I donated all of the money to one of the struggling youth centers I had been working at.

A few weeks later, I received a terse letter from Tams Witmark Publishing Company’s legal department asking who it was that had granted me permission to produce their property. They additionally demanded a formal accounting of the box office receipts.

I responded by sending the attorneys as sincere-sounding a letter of apology as I could manage, hand-written with a pencil on wrinkled, torn yellow notebook paper,. I wrote basically that I didn't understand that I needed permission to do the show since I was simply trying to raise money for underprivileged kids, which was true.

I never heard from them again.

Rightly or wrongly, that experience contributed to another of my dictums to young people: whatever it is, if it doesn't hurt you and doesn't hurt anyone else, and doesn't get you into big trouble, do it.

In 1976, the daughter of a friend of my father happened to ask me to help her apply to the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Given my own dismal undergraduate history, I have no idea why she sought my assistance, except that she might have somehow known I did some occasional writing.

In the process of editing her application forms, I was surprised to hear her suggest I submit an application myself. I pointed out that I didn’t have an undergraduate degree. She informed me that Harvard would occasionally admit a student to its graduate schools on the basis of life experience.

Intrigued by this, and imagining the prestige of a Harvard graduate degree, I familiarized myself with the Graduate School of Education curriculum, and applied.

I included numerous pages of notes, documentation, and letters of recommendation from anyone I could think of, as well as some local newspaper coverage I had received in connection with my work with the kids of Boston and New York. My cover letter of sorts was a long essay about how I would apply my graduate coursework to furthering my effectiveness in using the arts as a vehicle to help “problem” kids.

The young lady I had assisted was not accepted.

However, I was.

A few weeks after my submission, I was excited to receive a letter asking me to visit the school and meet with a member of the Admissions Committee. I don’t recall anything specific about the interview, other than the fact that the woman I met with seemed warm and friendly, and was a good listener. I do remember leaving the room believing I had presented myself effectively, and apparently this was true.

Another few weeks went by, and I received a letter with an official notice stating that I had been formally accepted to the Harvard Graduate School of Education as a candidate for a Masters degree in Education.

Currently, that notice is framed and hanging on my living room wall, right next to the only degree I ever completed: an Ed. M. from Harvard University in 1978.

And... the long road to Broadway continues next month.

Until then, take good care of yourself.

Thanks.

Peter Seidman