PART III: WHY I'M NOT YET A BROADWAY PRODUCER...

/There are many positive things I could say about my graduate school experience, but the most profound was my familiarization with the work of psychologist Carl Rogers.

Rogers, still alive at the time, had developed what he called client-centered therapy; in brief, this is a technique wherein the listening skills of the counselor lead the patient, or client, to become more aware of her feelings, and eventually accept them, and herself. One of Rogers' books, required reading for my counseling studies, was On Becoming a Person.

This book, along with my counseling courses, was to change my life and career, and ultimately the lives of thousands of kids I would work with, in more profound ways than I can possibly describe here.

Following Harvard, I moved back to New York in 1978. The Newton youth center had closed, and I had become intrigued with the idea of working with “professional children”, i.e. the kids who were actually appearing in the Broadway productions of the musicals I had been directing locally.

I rented an apartment on lower Madison Avenue in Manhattan, and, while trying to figure out how to meet and work with industry kids, I returned to my usual means of earning a living- playing piano. I had discovered that surviving as a pianist in New York means, in addition to playing in clubs and a bit of studio work, accompanying and coaching singers.

My musical theater experience had provided me with an extensive repertoire of vocal material, and largely through word of mouth, I developed a more than decent-sized practice of weekly private vocal coaching students. Even as the rest of my life unfolded, I continued working as a pianist and coach for the next twenty years.

One of the places I had applied for piano work was an intimate, upper east side restaurant that served only desserts. It was called Something Different, and had a small stage on which the waiters would take turns singing in between serving tables. Although the place wasn’t looking for a pianist at the time, I had an idea.

I asked the owner how she felt about having some of my younger vocal students perform songs for her customers in a showcase on the weekends. My proposal was that I would audition and select the kids, choose and arrange the songs, be the accompanist for the showcase, open it to the public on weekend afternoons, and we’d evenly divide whatever income the show attracted.

She agreed.

Soon after, I learned of a west side restaurant and bar called Beefsteak Charlie’s. It was said that this was where the kid casts of various Broadway shows would go with their parents to unwind after performances. One evening, hoping we might meet some of these kids and convince their parents to allow them to perform in our showcase, the owner of Something Different and I paid a visit.

Sure enough, while listening to a very young Nathan Lane performing cabaret-style, we met a sweet woman who was there with her daughter, 11-year-old Laura Dunn, one of the orphans in Broadway’s Annie. I was thrilled with the prospect of having Laura sing in my fledgling showcase, and even more so when her mother not only agreed, but surprised me by behaving as the antithesis of a stage mother; she volunteered to ask other members of Annie's children’s cast if they were interested as well.

Within a month, I had lined up all of the "orphans", including the star at the time, Allison Smith, who I auditioned backstage at the Alvin Theater, (subsequently re-named the Neil Simon). Soon, I had auditioned, and gladly accepted, all of the "Lost Boys" in Broadway's Peter Pan, starring Sandy Duncan, the full children's chorus of Evita, starring Patti Lupone, as well as kids from several other hit musicals of the day.

Our showcase, which I named “Beginnings” after the youth center in Massachusetts, additionally attracted a teenage Sara Jessica Parker who preceded Miss Smith in the starring role of Annie. Bright, funny, perceptive, open, and always real, Sara quickly became one of my favorite kids. Many years later, I would lecture about how those qualities explained her eventual and, I felt, inevitable success.

BEGINNINGS SHOWCASE featured in Cover STORY, NY TIMES ARTS & LEISURE SECTION 1981

I sent a release about the showcase to all the major newspapers and television stations. I was amazed that the first to respond was the much revered New York Times; a reporter covered one of our performances, and interviewed me at some length. This resulted in an article which appeared on that weekend's cover page of the Times' Arts and Leisure section.

More newspaper and television coverage followed, until one afternoon I received a call from David Powers, Annie's official publicist. All I remember from the conversation was him declaring, not unhappily, that I was getting more attention for his show than he was.

Our audiences began to include celebrities. Among others, I remember speaking briefly with Brooke Shields and her mother, Teri, following one of our performances.

One afternoon, I learned that Martin Charnin, Annie's director and lyricist, was planning to attend. This was due to the fact that in addition to working with the children in his Broadway cast, his own daughter, Sasha, herself a gifted performer, had been appearing in our showcase.

Martin's impending visit terrified me. I knew that if for any reason he didn't like what he saw and heard, we'd lose the Annie kids in a heartbeat, and probably most of our others. To my relief, he was all smiles from start to finish. At the end, he approached me and said: "Wonderful job." The praise was apparently sincere; a few days later, he called and asked me if I would create a musical arrangement of the Cole Porter standard, I Happen to Like New York, for a presentation he was directing for the New York Press Club. I did, and after the performance, he said: "Terrific arrangement."

I was obviously thrilled.

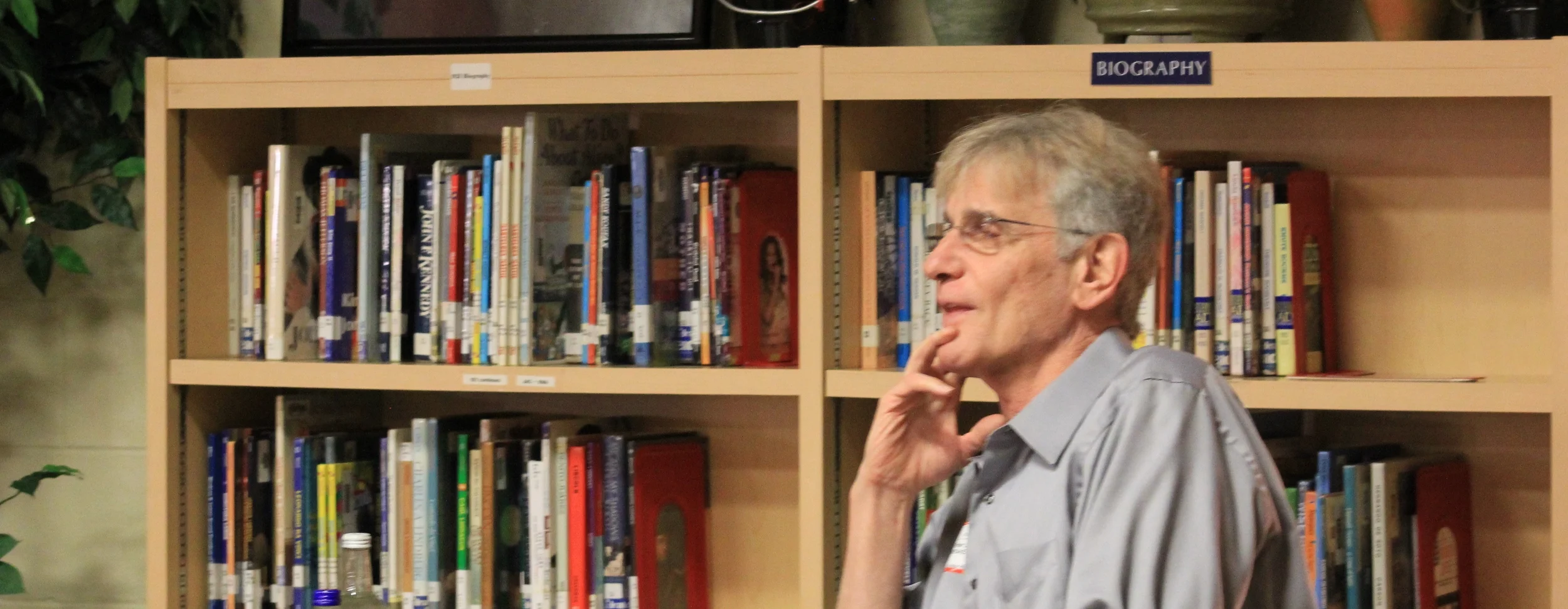

ACCOMPANYING SASHA CHARNIN

Ironically, the second person of such stature to compliment me during that period was Martin's collaborator, the composer of Annie, who was also the composer of Bye, Bye, Birdie and many other musicals and hit songs, Charles Strouse.

Charles' son, Nicholas, had been performing in my showcase, and I learned that Charles was conducting a song-writing workshop at the 92nd Street YMHA. I had begun writing some songs depicting the lives of kids in the industry, and one of these was inspired by the experiences of Annie's star, Allison Smith, who I had been working with. I knew Charles would appreciate the subject matter, since it had to do with his show, but I didn't know how he'd respond to the song-writing itself.

Bravely, I signed up for his class, and when it came my turn to play something, I stopped and said: "I'm not really a song-writer, but I thought you might find this interesting." I played the song, and he responded: "You're wrong. You are a song writer."

A few months later, the father of one of my former students, an attorney for the unions who negotiate with Broadway’s Shubert Organization, brought a few Shubert representatives to my downtown studio apartment where I played them a few more of my songs.

They responded: “We see lots of these presentations and honestly most of them are for shows that aren’t very good. This one is.”

After that moment, I began to write in earnest.

NEXT MONTH: FIRST THOUGHTS OF BROADWAY